In this study, I looked at variances in the dawn chorus in a natural versus urban setting. I chose my natural setting to be Tilden Regional park and my urban setting to be Memorial Glade on UC Berkeley’s campus. In both settings, I examined the number of bird species calling, the time of onset, and the length of two specific species’ calls, the American Robin (Turdus migratorius) and the Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis). Between the two locations, I saw a difference in the number of bird species calling during the dawn chorus, with the natural setting providing a greater number of species calling than the urban setting. Additionally, the onset times of the dawn chorus in the two locations differed substantially with the urban onset time starting earlier. Finally, I found that there was little variation in the call length of the American Robin between the two locations, but the Dark-eyed Junco showed a trend towards longer calls in the urban setting in comparison to the more natural setting.

Abstract

The dawn chorus is a prominent, mostly passerine, bird behavioral pattern just before sunrise. In a typical dawn chorus, all territorial males sing in synchrony until the light of the sunrise reaches a certain level at which the chorus stops and switches to more sporadic singing (Staicer et al., 1996).

There are numerous theories as to why birds choose to sing so early. These theories fall into three categories: intrinsic, environmental, and social. In the intrinsic hypothesis, the calls are thought to be initiated by circadian cycles of testosterone or self stimulation (Goodson, 1998). The environmental hypothesis concerns the quality of acoustics and lower predation risks when calling in large numbers in the early morning (Hutchinson, 2002). Lastly, the social hypothesis includes the use of the dawn chorus to defend territories, impress mates, and communicate with specific individuals (Staicer et al. 1996). None are mutually exclusive, and the importance of any one factor may differ by species.

It is known that sensory pollution is common in urban areas, and can affect animals in complex ways due to interactions between sensory stimuli, and behavioral feedback via neuronal and endocrine systems (Halfwerk et al., 2015). In this study, I investigate how urbanization affects the dawn chorus. I sample from two different environments: (1) a natural setting in Tilden Regional Park and (2) an urban setting on Memorial Glade on UC Berkeley’s campus. I analyze the diversity of species calling, the length of each species’ call, and the onset time of the dawn chorus. My hypothesis was that urban settings would have a less diverse dawn chorus with fewer species calling, longer calls in individual species, and an earlier onset in comparison to the natural setting.

Introduction

Figure 1. Map of urban setting: Memorial glade on UC Berkeley campus

Figure 2. Map of natural setting in Tilden Regional Park

Audio samples of the dawn chorus were collected on an iPhone 7 using the “Voice Memos” app.

Samples were recorded initially 15 minutes before and after the first light of the sunrise that day with the iPhone placed screen-down on a car roof. The first light times of the day used were according to the Sunrise and Sunset website (“Sunset and Sunrise Times”). I defined a natural setting as a location having little to no people, no artificial noise, and no artificial light and an urban setting as a populated area with noise and light pollution. I chose Tilden Regional Park as my natural site and Memorial Glade as my urban site. I picked these sites because I am familiar with them and they are within a 3.6-mile radius of each other, yet one was clearly more urbanized than the other. Therefore, minimizing variation due to distance in locations (i.e. within the same regional distribution) and focusing on type of environment; urban versus natural.

The dawn chorus at the urban location started prior to the standardized 15 minutes before first light, so revisitation of the field and modification of the procedure to instead start 2 hours prior to the first light to re-record occurred.

Previous studies have shown that there are intraspecific differences in song frequencies between open and forested habitats (Slabbekoorn et al., 2007). To account for this effect, both areas chosen to sample from were near open grass patches so song frequencies would be similar. Additionally, samples were taken in similar weather conditions — slightly windy, approximately 12.78 degrees C, and no rain.

For the urban setting, Memorial glade [Figure 1], UC Berkeley campus, CA 94707, coordinates: 34.873423, -122.259786 was chosen. Recordings were taken specifically across from Haviland Path, just Northeast of the East Asian Library on University dr. Tilden Regional Park [Figure 2], coordinates: 37.893879, -122.246450, was chosen as the natural setting, just behind the Brazilian Room on Anza View Rd. adjacent to the Island picnic area.

Bird species were identified using calls, referencing the “A. Rush Birds of the Bay Area 2014 (mp3).zip” file (A. Rush, 2014). Luscinia, a bioacoustics software that isolates the calls from recordings and reduces the background noise was used if a bird call was particularly difficult to hear. Data was compiled into google sheets and excel and graphical representations were made in R. From the recordings, the order of species calling, number of species, and onset times were extrapolated. Additionally, 2 specific bird species, American Robin and Dark-eyed Junco, were were present in both locations and their length of calls were documented to compare intraspecific call variations due to location.

Methods

Figure 3. Number of species according to location with t-test p-value.

Figure 4. Time of onset according to location with t-test p-value

Figure 5. Length of call by species in natural (Tilden) and urban (Memorial Glade) setting

Results

With the data collected, I’ve found that the diversity of calls in the dawn chorus in the natural compared to the urban setting differed [See Table 1 in Appendix].

Figure 3. Number of species according to location with t-test p-value.

In the more natural environment, there was an average of 9.34 bird species calling during the dawn chorus. In the more urban environment, there was an average of 6 birds calling during the dawn chorus. Although there is no significant difference, there is a clear trend. In the more natural setting, a Steller’s Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) was heard in almost every sample while in the urban setting it was not. In the urban setting, an Orange-crowned Warbler (Vermivora celata) was heard, but was missing from the dawn chorus recordings in the natural setting.

Additionally, I found that in the urban location, the dawn chorus started earlier than in the natural setting (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Time of onset according to location with t-test p-value

On average, in the urban setting, the dawn chorus started 97.34 minutes prior to first light, while in the natural setting it started 18.34 minutes prior to the first light. That is a difference of 79 minutes between the mean dawn chorus onset times in the urban versus natural environment.

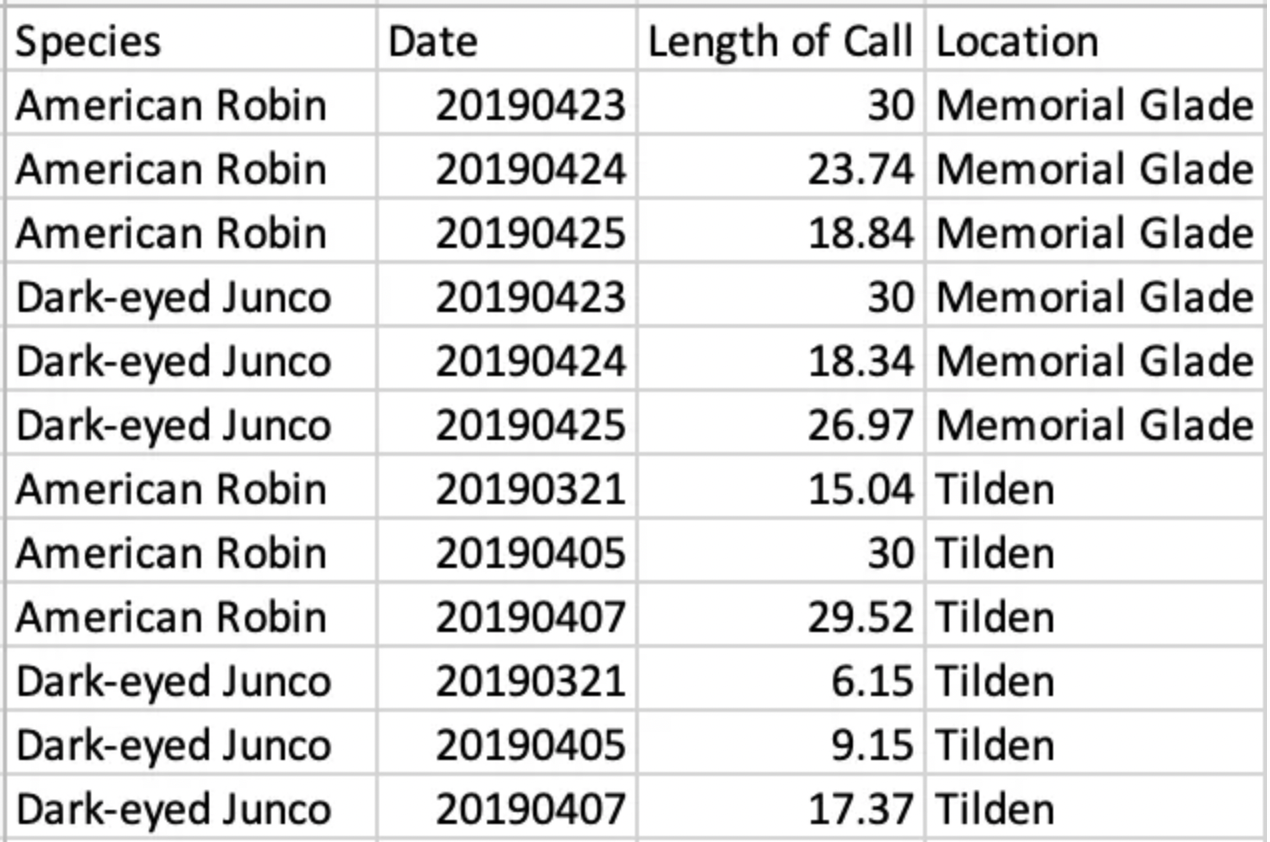

Finally, I looked at two species’ length of calls in both the urban and natural setting: the American Robin and the Dark-eyed Junco [Figure 5]. I found that there was little difference in the calling of the American Robin between locations, but there was a trend in the Dark-eyed Junco’s calls towards longer calls in the more urban location [See Table 2 in Appendix].

Discussion

The natural setting, Tilden Regional Park, had a dawn chorus start closer to the first light by 79 minutes when compared to a the more urban Memorial glade. This supports my hypothesis that an urban setting will result in an earlier onset of the dawn chorus. This may be occurring due to light pollution and noise pollution in the area, forcing the dawn chorus much earlier as birds wake up earlier and need to call earlier to be heard.

Additionally, there was a difference in the diversity of species calling. The natural setting had 3.4 more species call compared to the urban setting. This supports my hypothesis that a more urban location will result in a less diverse dawn chorus. This may be due to less available resources to provide suitable niches for birds in an urban setting. These two communities are clearly different, in the natural environment, I detected Steller’s Jay, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Fox Sparrow, Mourning Dove, Black-headed Grosbeak, Scrub Jay, Wild Turkey, Golden-crowned Sparrow, Black Phoebe, and Canada Goose, but not in the urban environment. And Orange-crowned Warbler and Brewer’s Blackbird were detected in the urban environment but not in the natural environment.

Finally, there was negligible difference in American Robins’ calling length between the two locations, but there was an obvious trend in Dark-eyed Juncos that called longer in urban settings. The data from the Dark-eyed Juncos support my hypothesis that birds in a more urban environment will result in longer calls. This may be the result of noise pollution drowning out calls and birds attempting to compensate for that with longer calls. American Robins, however, do not fit this trend in my data because they start the dawn chorus and were already calling for most of the standardized thirty minute time frame in the natural setting, so when compared to the urban setting the difference seemed negligible. Further research into the length of American Robin’s calls would be necessary to conclusively state whether or not American Robins show this trend too.

Though most of my findings support my hypothesis, a better way of testing for the onset of the dawn chorus would have been to start a standard of 2 hours prior to the first light for both locations. Also, I would have recorded all dawn choruses within or near the same month to reduce sunrise time variation and avoid seasonal differences in bird populations. I additionally would have shifted my natural setting location in Tilden further away from roads, specifically Wildcat Canyon Road, because it became rather busy around 6 am thus contributing to the background noise and potentially startling the birds. All of this culminates to make this location in Tilden a suboptimal natural setting. Increasing my sample size over my three samples per setting and sampling from another two locations, one with similar natural qualities and the other with similar urban characteristics, would add more legitimacy to my data as well.

All of my findings regarding the dawn chorus in this study are results of sensory pollution. Human acoustic footprints are far reaching and have been proven to affect various animals’ habitat quality, stress levels, and reproductive success. Female tree swallows have been found to produce fewer eggs (Injaian et al., 2018) and Greater sage-grouse, a bird species of particular conservation concern, stress-levels and choice of otherwise suitable habitats have been impacted by noise pollution (Blickley et al., 2012). Additionally, studies on marine mammals have shown that deep diving cetaceans may behaviorally respond to sonar waves by rapidly ascending from deep depths upon exposure, resulting in nitrogen gas-bubble formations in tissue and acute death (Jepson et al., 2003 and Kvadsheim, P., 2012). My findings of altered behavior in animals due to sensory pollution are not uncommon. Hopefully this study will help inform consequences of sensory pollution on birds and their behavior and will contribute to a larger discussion about the effects of urbanization on wildlife populations.

References

“A. Rush Birds of the Bay Area 2014 (mp3).zip file.” Natural History of Vertebrates (Spring 2019)/Lab Materials, https://bcourses.berkeley.edu/courses/1479319/files/folder/Lab%20Materials?preview=74394065

Blickley, J., Word, K., Krakauer, A., L Phillips, J., Sells, S., Taff, C., C Wingfield, J., and Patricelli, G. (2012). Experimental Chronic Noise Is Related to Elevated Fecal Corticosteroid Metabolites in Lekking Male Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), Research Gate, PloSone.7. e50462.10.1371/journal.pone.0050462.

Goodson, J. L. (1998). Territorial aggression and dawn song are modulated by septal vasotocin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in male Field Sparrows (Spizella pusilla). Hormones and Behavior, 34(1), 67–77.

Halfwerk, W., and Slabbekoorn,H. “Pollution Going Multimodal: the Complex Impact of the Human-Altered Sensory Environment on Animal Perception and Performance.” Biology Letters, vol. 11, no. 4, 2015, pp. 20141051–20141051., doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.1051.

Hutchinson, J. “Two Explanations of the Dawn Chorus Compared: How Monotonically Changing Light Levels Favour a Short Break from Singing.” Animal Behaviour, vol. 64, no. 4, 2002, pp. 527–539., doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.3091.

Injaian, A., Poon,L., and Patricelli,G. Effects of experimental anthropogenic noise on avian settlement patterns and reproductive success, Behavioral Ecology, Volume 29, Issue 5, September/October 2018, Pages 1181–1189, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ary097

Jepson PD., Arbelo M., Deaville R., et al. Gas-bubble lesions in stranded cetaceans. Nature 2003; 425:575–6.

Kvadsheim, P. “Estimated Tissue and Blood N2 Levels and Risk of Decompression Sickness in Deep-, Intermediate-, and Shallow-Diving Toothed Whales during Exposure to Naval Sonar.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 3, 2012, doi:10.3389/fphys.2012.00125.

Slabbekoorn, H., Yeh, P., and Hunt, K. Sound Transmission and Song Divergence: A Comparison of Urban and Forest Acoustics, The Condor: Ornithological Applications, Volume 109, Issue 1, 1 February 2007, Pages 67–78, https://doi.org/10.1650/0010-5422(2007)109[67:STASDA]2.0.CO;2

“Sunset and Sunrise Times.” Sunrise and Sunset for Any Location in the World, sunrise-sunset.org/.

Appendix

Table 1: Number of species calling (n.species), start time of the chorus (Start), first light time that day (First.Light), and the difference in minutes between the start time of the chorus and the first light time (time.difference).

Table 2: The length of calls of American Robins and Dark-eyed Juncos in both locations.